Statement

The Equality Commission has published a Statement on Key Inequalities in Employment in Northern Ireland which highlights our assessment of inequalities and differences in employment faced by equality groups across the Section 75 equality categories in Northern Ireland.

The Equality Commission has published a Statement on Key Inequalities in Employment in Northern Ireland which highlights our assessment of inequalities and differences in employment faced by equality groups across the Section 75 equality categories in Northern Ireland.

Download our Statement on Key Inequalities in Employment:

Key Inequalities

Alongside a number of differences and wider inequalities, fourteen key inequalities have been identified for employment from data spanning 2007-2016:

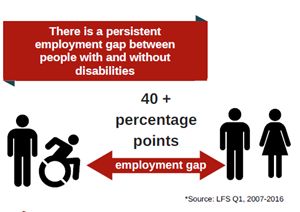

There is a persistent employment gap between people with and without disabilities

People with a disability are more likely to be not working and not actively looking for work (economically inactive) than people without disabilities; consequently, they are much less likely to be in employment than people without disabilities. In addition, the gap in the employment rate between people with and without disabilities is persistent, having shown little change between 2006 and 2016.

For people with disabilities, gaps in educational attainment may partially account for the large employment gap between people with and without disabilities. However, even when attainment is accounted for, participation in employment is still lower for people with disabilities than non-disabled people with equivalent qualifications.

People with disabilities, however, face wider barriers such as access to transport, the physical environment and limited support in employment, all of which can impact on their ability to participate in employment.

Among people with disabilities, people with mental health issues and/or a learning disability are less likely to be employed compared to people with hidden disabilities, progressive or other disabilities, physical disabilities and / or sensory disabilities.

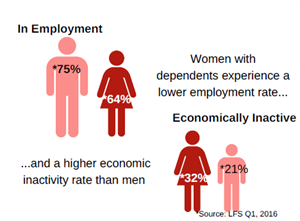

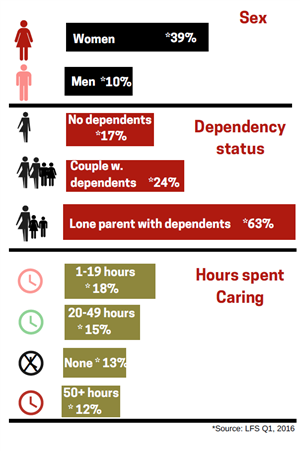

Women experience a lower employment rate and a higher economic inactivity rate when they have dependents

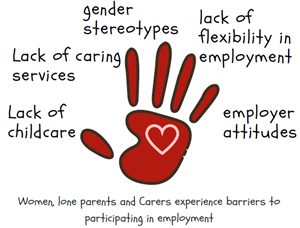

Factors explaining this are likely to be linked to the disproportionate share of caregiving by women, with gender stereotypes relating to the role of the mother as primary caregiver and father as the earner that may result in higher rates of economic inactivity among women.

Barriers may also be attributed to the cost and availability of childcare, with Northern Ireland having one of the lowest levels of available childcare and being one of the most expensive regions for childcare in the UK. For women, paid work may not be considered worthwhile if a significant proportion of female-generated income is being spent on childcare.

In addition, qualifications and confidence are an issue for women from disadvantaged backgrounds; low-skilled and low-paid jobs often do not allow women to afford paid childcare and may offer lower levels of flexibility to accommodate caregiving. In addition, the current social welfare system may inhibit labour market participation, as women are unsure if work-based income would exceed benefits-based income, particularly when the cost of childcare and risk of losing housing benefits is taken into account.

Lone parents with dependents experience barriers to their participation in employment

Lone parents with dependents experience a lower employment rate and a higher economic inactivity rate, particularly for women who constitute the majority of lone parents.

Factors explaining this are similar to that experienced by women with dependents but further compounded for lone parents with dependents who have sole responsibility for the care of their child(ren).

Carers experience barriers to participating in employment

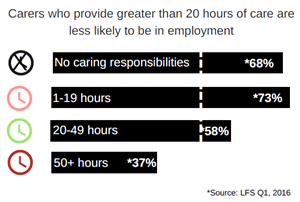

Barriers for carers increase with the volume of care provided. Carers who provide more than 20 hours of care per week are less likely to be in employment and more likely to be economically inactive than those who do not provide care.

Barriers for carers increase with the volume of care provided. Carers who provide more than 20 hours of care per week are less likely to be in employment and more likely to be economically inactive than those who do not provide care.

For carers, a lack of flexibility in the workplace to enable them to manage caring responsibilities and a lack of suitable care services are major barriers to participation. However, attitudinal barriers to carers from employers and work colleagues also represent a barrier to employment.

These factors result in some carers giving up work, the consequence of which is negative impacts on their finances, health and wellbeing.

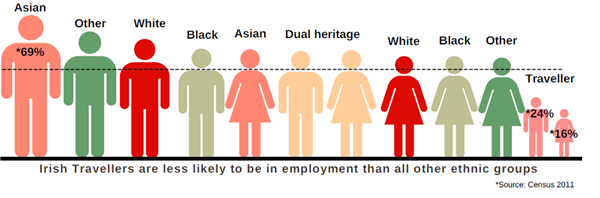

Irish Travellers are less likely to be in employment than all other ethnic groups

Irish Travellers are less likely to be in employment and more likely to be economically inactive than other ethnic groups. Traveller women, in particular, are less likely to participate in employment and are more likely to be economically inactive than women from all other ethnic groups.

Low educational attainment may partially account for the large employment gap between Irish Travellers and other ethnic groups. Another major barrier is prejudice and discrimination both in society and in the workplace with discriminatory attitudes preventing them from participating in employment. In addition, a greater traditional emphasis on family and home, as well as cultural resistance to the use of formal childcare present further barriers to the participation of Irish Travellers in employment.

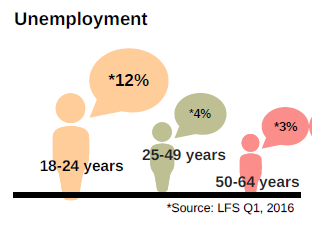

Those aged 18-24 years have higher unemployment rates than those aged 25 years and older

Those aged 18-24 years old have higher unemployment rates than those aged 25 years and older.

Youth employment was identified as a key inequality in our previous 2007 Statement on Key Inequalities.

Youth unemployment is associated with lifelong problems, such as worklessness, poverty, limited employment opportunities, low wages, lower average life satisfaction and ill health.

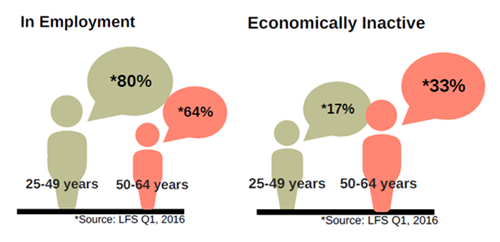

Those aged 50-64 years are less likely to be in employment and more likely to be economically inactive than those aged 25-49

Older people, aged 50-64 years also experience age-related inequalities in relation to participation in employment, with this age group less likely to be in employment and more likely to be economically inactive than those aged 25-49 years old.

Older people, aged 50-64 years also experience age-related inequalities in relation to participation in employment, with this age group less likely to be in employment and more likely to be economically inactive than those aged 25-49 years old.

For older people, the main work-related barriers were viewed to be ‘difficulty in getting a job’; ‘being made redundant’; and, ‘job insecurity’.

However, increases in economic inactivity among this age group may be linked to long-term sickness, rising retirement age and the provision of informal care, such as for children as well as older and/or disabled relatives.

Women, lone parents with dependents & carers providing less than 49 hours of care are more likely to be in part-time work

Women are more likely to be in part-time employment than men. Lone parents with dependent children are more likely to be in employment on a part- time basis.

In addition, carers who provide less than 49 hours of unpaid care are more likely to work part-time.

While part-time working is one of a number of means by which women, lone parents, and carers balance employment with caring responsibilities, it can negatively influence progression in employment, with women, lone parents and carers sometimes perceived negatively for asking for flexible working.

Women, lone parents and carers working part-time are also at risk of low pay and precarious employment, as many part-time jobs are typically associated with the minimum wage and atypical contracts.

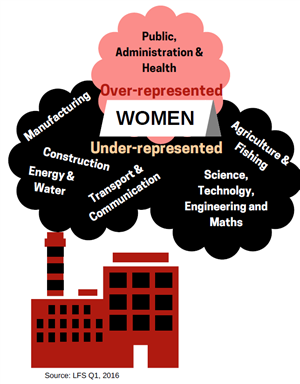

Women experience industrial segregation in employment

Women are under-represented in industries associated with Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) such as Manufacturing, Transport and Communication, Energy and Water and Construction.

Stereotyping and bias within our culture and particularly within male-dominated engineering and technology sectors, has been cited as one factor presenting barriers for women within these industries.

In addition, young women are less likely to choose to study STEM subjects at further and higher education compared to young men thus decreasing their availability for high-level STEM jobs, where men outnumber women by nearly three to one.

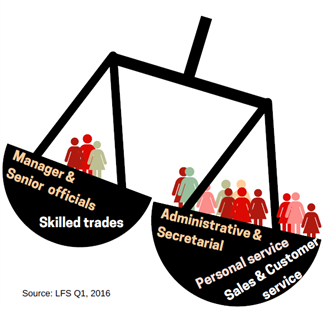

Women and lone parents experience occupational segregation in employment

Women are under-represented in the highest paid and highest status occupations such as ‘Managers and Senior Officials’ and are over-represented in occupations that are more likely to be lower status and lower paid, such as ‘Administrative and Secretarial’, ‘Personal Service’ and ‘Sales and Customer Service’. Moreover, women are more likely to report underemployment in their chosen occupation compared to men.

Women are under-represented in the highest paid and highest status occupations such as ‘Managers and Senior Officials’ and are over-represented in occupations that are more likely to be lower status and lower paid, such as ‘Administrative and Secretarial’, ‘Personal Service’ and ‘Sales and Customer Service’. Moreover, women are more likely to report underemployment in their chosen occupation compared to men.

Lone parents also experience occupational segregation in employment, with lone parents with dependent children mostly employed in ‘Personal Service’ and ‘Elementary’ occupations.

Caregiving has been identified as one factor influencing occupational segregation with women and lone parents choosing occupations allowing sufficient flexibility to balance the demands of caregiving. This may have a potential impact on the sustainability of employment, with women and lone parents having to consider pay and career progression with flexibility in employment.

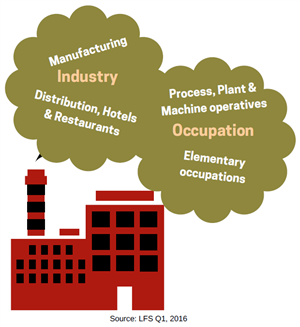

Migrant workers, particularly those from Eastern European countries, are subject to industrial and occupational segregation

Migrant workers, particularly Eastern Europeans are over-represented in low-paid, low status jobs such as ‘Process, Plant and Machine Operatives’ and ‘Elementary’ occupations and in low paid-industry sectors such as the ‘Manufacturing’ industry sector and the ‘Distribution, Hotels and Restaurants’ industry sector.

While migrant workers tended to be working in higher-level occupations in their home country, it has been posited that gaining a lower level job in Northern Ireland is treated as a step toward gaining higher-level employment in the future.

Migrant workers and refugees face multiple barriers to employment

Migrant workers and refugees face numerous barriers to participating in and sustaining employment in Northern Ireland. Recognition of qualifications is an issue for migrant workers and refugees progressing in employment. In addition, inadequate language proficiency is a major barrier for migrant workers and refugees qualifying for and participating in employment, particularly where the standard of English proficiency for particular professions is set very high.

Uncertainty among employers about an employee’s ‘right to work” may create perceived legislative barriers for foreign nationals accessing and sustaining employment in Northern Ireland. In addition, the long transition period between seeking and being granted asylum, represents a long time out of employment, which can deskill refugees. This can create a lack of confidence and may require them to retrain or gain new skills prior to seeking employment.

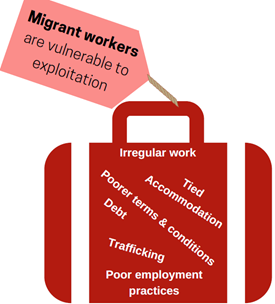

Migrant workers are vulnerable to exploitation

Many migrant workers who are agency workers are confined to temporary and irregular work, including zero hour contracts. Many face poorer terms and conditions than local workers and are vulnerable to poor employment practices, including a lack of written contracts, long-working hours, non-payment of wages and problems accessing statutory entitlements such as leave.

In addition, human trafficking is an issue in Northern Ireland, with evidence of practices that constitute forced labour of migrant workers. Common means of forcing people to work include withholding personal documents and forcing migrant workers to pay off debt incurred from ‘borrowing’ money to secure employment. In addition, migrant workers in tied accommodation are also vulnerable to exploitation.

Factors associated with exploitation include an individual’s legal status, a lack of language skills, limited access to social networks and a lack of local knowledge.

Prejudicial attitudes both within and outside the workplace are experienced by people...

People with disabilities are more likely to experience prejudice in employment than those without disabilities. Among people with disabilities, people with mental health issues are most likely to be viewed negatively as a work colleague or boss. This stigma and prejudice may impact on the ability of people with disabilities to sustain employment, with disability-related discrimination complaints representing the highest number of enquiries, with respect to employment, to the Equality Commission’s Discrimination Advice Team.

People with disabilities are more likely to experience prejudice in employment than those without disabilities. Among people with disabilities, people with mental health issues are most likely to be viewed negatively as a work colleague or boss. This stigma and prejudice may impact on the ability of people with disabilities to sustain employment, with disability-related discrimination complaints representing the highest number of enquiries, with respect to employment, to the Equality Commission’s Discrimination Advice Team.

Women experience prejudice, discrimination and harassment in the workplace; including discrimination due to pregnancy and maternity. Women have reported negative employment experiences such as: failure to consider the risks to health and safety of pregnant employees; being overlooked for promotion or otherwise side-lined; dilution of work responsibilities; being denied training; actions which impact negatively on earnings such as, changes to working hours, non-payment or reduction of pay rise or bonus payments; and, being subjected to negative or inappropriate comments.

Trans people face prejudice and hostility in employment and are less likely to be open about their gender identity in the workplace. Ignorance of Trans issues from employers and work colleagues is a key issue in Trans people participating in and sustaining employment.

Lesbian, gay and bisexual employees are subject to prejudicial attitudes in the workplace. Lesbian, gay and bisexual people often face negative comments and bullying at work due to their sexuality, and may be reluctant to come out in the workplace due to fears of victimisation. Prejudicial attitudes may impact on the ability of lesbian, gay and bisexual people to participate in employment, sustain employment and progress in employment. Many of the barriers and challenges in employment faced by lesbian, gay, bisexual and Trans people can be linked back to negative experiences in education.

People from minority ethnic groups and migrant workers are subject to prejudice and discrimination in employment. Prejudicial attitudes have been expressed toward Irish Travellers, migrant workers and minority ethnic groups. Racial prejudice and discrimination can impact on the ability of minority ethnic groups and migrant workers to participate in employment, sustain employment and progress in employment. Racial prejudice has been identified in accessing employment and in experiences of racial harassment and intimidation in workplaces.

Prejudicial attitudes and/or discrimination on the grounds of religious belief may impact on experiences within the workplace. Prejudicial attitudes toward those of different religious beliefs is present in Northern Ireland, particularly sectarianism and islamophobia. Prejudicial attitudes, harassment and, intimidation can create a climate of fear which can impact on a person’s ability to sustain employment, particularly where individuals are reluctant to speak out due to fears of further victimisation.

Data Gaps

An important caveat is that there remain significant and specific data gaps across a number of themes in relation to a number of equality groups, specifically: gender identity and sexual orientation. In addition, there is a lack of data disaggregation in relation to ethnicity; and, dependency status. These shortfalls limit the Commission’s ability to draw robust conclusions about inequalities, and/or progress in addressing the same across the full range of equality categories and groups.

Research

In compiling this Statement, the Commission has drawn on a wide range of sources including research reports from government departments, the community and voluntary sectors, academic research and the Commission’s own research archive. In addition, we contracted independent research by Naper University, Edinburgh, and undertook a detailed analysis of the Labour Force Survey by each equality ground. Stakeholder engagement and a public consultation process also played a key role in the formation of this Statement.

Download research 'Employment Inequalities in Northern Ireland':

This statement on Key Inequalities in Employment is part of a series of statements which will examine key issues across various areas where people in Northern Ireland face inequality. It will update the our work on key inequalities carried out in 2007 (pdf)

See our statements on:

<

Employment research and investigations

<

Employment landing page